Asian bonds have had a good run so far this year, producing a total return of 7.8% according to J.P. Morgan Asia Credit Index (JACI). But, looking back over the last three years, yields and spreads have steadily declined, so much so that “high yield” has become an oxymoron!

That has raised the question in the minds of many people: Is there a bubble in Asian fixed income?

The “B” word has been applied variously to different asset markets, such that it has become an amorphous thing … one that everyone talks about all the time, but no one knows precisely what it means! Let us try to keep the dreaded word in perspective for our discussion. One definition of a bubble is when the prices are far in excess of the fundamental value of the assets. Another way to look at a bubble is as an unsustainable and fast rise in prices. Either way, a bubble carries the potential to hurt investors when it eventually suddenly bursts.

Keeping this in mind, let us examine the evidence in the Asian U.S. Dollar bond markets. The first evidence for the existence of a bubble is the contraction in both yields and spreads. It is true that the current yield to maturity of 4.6% for JACI seems too tight, particularly when compared with the high level of 11% during the Global Financial Crisis. But if we disregard the spike in yields during the GFC and the period when the interest rates were slashed in its aftermath, average yields have moved in a narrower range of 4.2% to 5.5% in the last four years and the current yield is near the middle of this range.

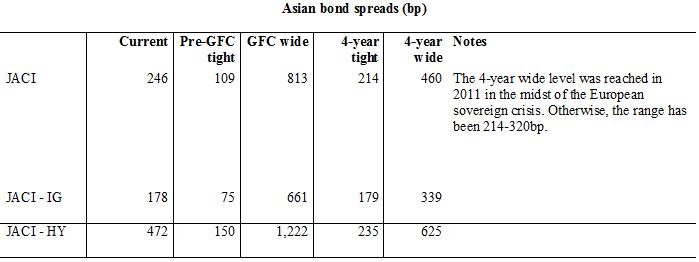

Similarly, if we consider the history of spreads, the current spreads over Treasury of 243bp appears tight when compared with the GFC high of over 800bp. But in the last four years, they have ranged between 214bp and 450bp; and if we disregard the mini-spike during the European sovereign crisis, they have moved between 214bp and 320bp. Compared to this range, the current spreads do not appear so alarming. In fact, they are more than double the tight levels of 109bp reached in 2007 before the GFC.

That has raised the question in the minds of many people: Is there a bubble in Asian fixed income?

The “B” word has been applied variously to different asset markets, such that it has become an amorphous thing … one that everyone talks about all the time, but no one knows precisely what it means! Let us try to keep the dreaded word in perspective for our discussion. One definition of a bubble is when the prices are far in excess of the fundamental value of the assets. Another way to look at a bubble is as an unsustainable and fast rise in prices. Either way, a bubble carries the potential to hurt investors when it eventually suddenly bursts.

Keeping this in mind, let us examine the evidence in the Asian U.S. Dollar bond markets. The first evidence for the existence of a bubble is the contraction in both yields and spreads. It is true that the current yield to maturity of 4.6% for JACI seems too tight, particularly when compared with the high level of 11% during the Global Financial Crisis. But if we disregard the spike in yields during the GFC and the period when the interest rates were slashed in its aftermath, average yields have moved in a narrower range of 4.2% to 5.5% in the last four years and the current yield is near the middle of this range.

Similarly, if we consider the history of spreads, the current spreads over Treasury of 243bp appears tight when compared with the GFC high of over 800bp. But in the last four years, they have ranged between 214bp and 450bp; and if we disregard the mini-spike during the European sovereign crisis, they have moved between 214bp and 320bp. Compared to this range, the current spreads do not appear so alarming. In fact, they are more than double the tight levels of 109bp reached in 2007 before the GFC.

Compared to the U.S. domestic bonds, Asian spreads still offer value. Asian investment-grade corporate bonds, for example, trade at 180bp over Treasury, while spreads for U.S. industrial bonds with equivalent credit quality and maturity trade at spreads of 100bp.

When we consider the fundamentals, another key factor is the default rate for bonds. According to Moody’s, the global high-yield default rate was 2.1% for July 2014, well below the historical average of 4.7%. In Asia-Pacific, Moody’s predicts a default rate of 3.3%.

While such low default rates are one of the supports for the current tight spreads, we must remember that they are themselves partly the result of loose liquidity conditions and easy monetary policy. That brings us to the one of the key reasons to question whether the Asian bond market might collapse in a bubble-like fashion when rates start rising and liquidity begins to ebb. It is doubtless true that the bond valuations have benefited from the falling rates. In 2014 so far, of the 7.8% return generated by Asian bonds, 3.6% has come from a fall in Treasury yields and the rest from tightening spreads.

This comfortable environment would change as the Fed starts raising rates in the second half of 2015. Not only will longer-duration bonds face capital losses, but weaker companies would find it more challenging to roll over maturing debt – in turn leading to higher default rates.

It is based on such fears that some predicted a mass migration of funds from fixed income to equity, calling it the Great Rotation. But so far, in the Asian bond markets, there has been scant evidence of such a shift. New issue volumes are touching record levels, with USD 120 bn of new bonds so far this year, representing a growth of 35% over the same period last year. Although private banks have taken up only 9.7% of new issues this year, down from 16.2% and 13.9% in the last two years, the gap has been more than adequately filled by institutional funds.

At a very fundamental level, Asian economic growth is holding up reasonably well, although all eyes are on China’s and India’s growth rates to see how these two economies perform. For the Asian bond market, China is a key variable, particularly the Chinese property sector.

So, finally, is there a bubble or not in Asian bonds? Although Asian bond valuations are stretched at the moment, they are not beyond belief and entirely divorced from fundamental factors. Some of the supporting factors such as rates and high liquidity will diminish over the next two years, but I believe the correction would be orderly and not a sudden collapse. Asian bond valuations may be tight, but they are not a bubble.

When we consider the fundamentals, another key factor is the default rate for bonds. According to Moody’s, the global high-yield default rate was 2.1% for July 2014, well below the historical average of 4.7%. In Asia-Pacific, Moody’s predicts a default rate of 3.3%.

While such low default rates are one of the supports for the current tight spreads, we must remember that they are themselves partly the result of loose liquidity conditions and easy monetary policy. That brings us to the one of the key reasons to question whether the Asian bond market might collapse in a bubble-like fashion when rates start rising and liquidity begins to ebb. It is doubtless true that the bond valuations have benefited from the falling rates. In 2014 so far, of the 7.8% return generated by Asian bonds, 3.6% has come from a fall in Treasury yields and the rest from tightening spreads.

This comfortable environment would change as the Fed starts raising rates in the second half of 2015. Not only will longer-duration bonds face capital losses, but weaker companies would find it more challenging to roll over maturing debt – in turn leading to higher default rates.

It is based on such fears that some predicted a mass migration of funds from fixed income to equity, calling it the Great Rotation. But so far, in the Asian bond markets, there has been scant evidence of such a shift. New issue volumes are touching record levels, with USD 120 bn of new bonds so far this year, representing a growth of 35% over the same period last year. Although private banks have taken up only 9.7% of new issues this year, down from 16.2% and 13.9% in the last two years, the gap has been more than adequately filled by institutional funds.

At a very fundamental level, Asian economic growth is holding up reasonably well, although all eyes are on China’s and India’s growth rates to see how these two economies perform. For the Asian bond market, China is a key variable, particularly the Chinese property sector.

So, finally, is there a bubble or not in Asian bonds? Although Asian bond valuations are stretched at the moment, they are not beyond belief and entirely divorced from fundamental factors. Some of the supporting factors such as rates and high liquidity will diminish over the next two years, but I believe the correction would be orderly and not a sudden collapse. Asian bond valuations may be tight, but they are not a bubble.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed