This is the reproduction of an article published in IFR Asia.

Investors in Asian bonds got an unwelcome gift on New Year’s Day: Chinese property developer Kaisa Group announced that it had defaulted on a loan from HSBC.

The Kaisa tragedy had been unfolding since early December, when the company first halted trading in its shares and announced that Shenzhen authorities had blocked sales at three of its projects. Sino Life, an insurance company based in Shenzhen, then stepped in with US$215m to raise its stake from 18.75% to 29.96%, raising hopes that the bans would be soon removed. Even when Kaisa’s chairman resigned on December 11, there were no immediate concerns over Kaisa’s liquidity, based on the company’s last reported cash balance of Rmb11bn (US$1.75bn) at the end of June 2014.

Since then, however, there was a barrage of negative developments that neither Kaisa nor Sino Life could staunch. Shenzhen expanded its restrictions on Kaisa, onshore banks began legal proceedings to freeze Kaisa’s bank balances and assets, some project partners began to cancel their joint ventures and demand refunds. By the end of the month, the CFO and the vice chairman had quit – an important development since they had been key contact points for the financial market.

Yet, there was no actual default – until January 1st when the company announced that it had failed to meet HSBC’s demand for immediate repayment of a HK$400m (US$51.5m) loan due to the earlier resignation of the company’s chairman. After that, the company failed to repay an onshore trust loan. The offshore US dollar bondholders were directly affected on January 8, when the company did not pay a US$23m coupon. These amounts were trifling when compared with its June cash balance, but the company could still not meet them.

Throughout this saga, Kaisa’s offshore US dollar bonds fell to a low of about 30 cents. They have since recovered to about 60-70 cents after Sunac China, another property company, agreed to take a 49% stake and Kaisa paid the coupon within the 30-day grace period. The company has appointed a financial advisor and the market hopes that the restructuring of the bonds would not be too onerous on the investors.

Even as the Kaisa story has yet to reach its denouement, it is likely to have long-lasting implications. To start with, Kaisa may well turn out to be the first default in the Chinese property sector if the proposed restructuring of bond terms turns out to be a haircut in disguise. Previously, there have been several close shaves, but only three other property companies (Greentown China, SRE Group and, currently, underground mall developer Renhe Commercial) have bought back their bonds at 80-85 cents, widely seen as reasonable levels.

But Kaisa is also the first offshore bond issuer whose downfall was triggered by the actions of a local government in China. While no one has a full explanation of the actions of the Shenzhen authorities, the way the restrictions were expanded to cover multiple aspects of the business sent a clear message that the government intends to take strong action against Kaisa.

This means that investors have to assess not only business risks, but also pay specific attention to corporate governance risks. The Kaisa case has indeed taken them by surprise, as there had been no major corporate governance problems in the property sector so far. Agile Properties had alerted investors to the potential for such problems late last year, but they had been reassured when Agile had taken quick and firm measures to raise equity from the controlling shareholders’ family and demonstrate the support of its banks.

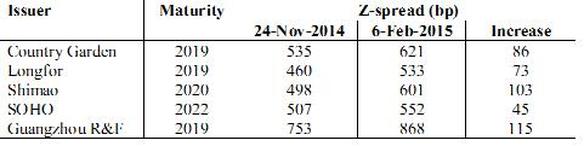

In the meantime, the cost of capital for the sector has increased sharply since late-November. (See Table.) While some of this increase may be reversed later this year if the property sector recovers, new debt raised in the meantime will have to bear this increased cost.

The Kaisa tragedy had been unfolding since early December, when the company first halted trading in its shares and announced that Shenzhen authorities had blocked sales at three of its projects. Sino Life, an insurance company based in Shenzhen, then stepped in with US$215m to raise its stake from 18.75% to 29.96%, raising hopes that the bans would be soon removed. Even when Kaisa’s chairman resigned on December 11, there were no immediate concerns over Kaisa’s liquidity, based on the company’s last reported cash balance of Rmb11bn (US$1.75bn) at the end of June 2014.

Since then, however, there was a barrage of negative developments that neither Kaisa nor Sino Life could staunch. Shenzhen expanded its restrictions on Kaisa, onshore banks began legal proceedings to freeze Kaisa’s bank balances and assets, some project partners began to cancel their joint ventures and demand refunds. By the end of the month, the CFO and the vice chairman had quit – an important development since they had been key contact points for the financial market.

Yet, there was no actual default – until January 1st when the company announced that it had failed to meet HSBC’s demand for immediate repayment of a HK$400m (US$51.5m) loan due to the earlier resignation of the company’s chairman. After that, the company failed to repay an onshore trust loan. The offshore US dollar bondholders were directly affected on January 8, when the company did not pay a US$23m coupon. These amounts were trifling when compared with its June cash balance, but the company could still not meet them.

Throughout this saga, Kaisa’s offshore US dollar bonds fell to a low of about 30 cents. They have since recovered to about 60-70 cents after Sunac China, another property company, agreed to take a 49% stake and Kaisa paid the coupon within the 30-day grace period. The company has appointed a financial advisor and the market hopes that the restructuring of the bonds would not be too onerous on the investors.

Even as the Kaisa story has yet to reach its denouement, it is likely to have long-lasting implications. To start with, Kaisa may well turn out to be the first default in the Chinese property sector if the proposed restructuring of bond terms turns out to be a haircut in disguise. Previously, there have been several close shaves, but only three other property companies (Greentown China, SRE Group and, currently, underground mall developer Renhe Commercial) have bought back their bonds at 80-85 cents, widely seen as reasonable levels.

But Kaisa is also the first offshore bond issuer whose downfall was triggered by the actions of a local government in China. While no one has a full explanation of the actions of the Shenzhen authorities, the way the restrictions were expanded to cover multiple aspects of the business sent a clear message that the government intends to take strong action against Kaisa.

This means that investors have to assess not only business risks, but also pay specific attention to corporate governance risks. The Kaisa case has indeed taken them by surprise, as there had been no major corporate governance problems in the property sector so far. Agile Properties had alerted investors to the potential for such problems late last year, but they had been reassured when Agile had taken quick and firm measures to raise equity from the controlling shareholders’ family and demonstrate the support of its banks.

In the meantime, the cost of capital for the sector has increased sharply since late-November. (See Table.) While some of this increase may be reversed later this year if the property sector recovers, new debt raised in the meantime will have to bear this increased cost.

Excluding Kaisa, about US$2bn of offshore bonds (US dollar and CNH) from China’s property sector are due for repayment in 2015. As financing conditions tighten, not all issuers may find it easy to refinance maturing bonds. The Kaisa issue has made it more difficult for lower-rated borrowers to raise financing at a reasonable cost.

It is also possible that investors would demand tighter covenants on future high-yield bond issues from China. For instance, offshore interest reserve accounts would be one way to address the split between onshore and offshore cash balances – a key concern in times of stress. Such reserves would give issuers and investors more time to sort out problems instead of pushing the issuers into immediate defaults. Investors may also begin to look critically at definitions of change of control and perhaps demand listing suspensions to be included as events of default.

While the underlying structural subordination of offshore bonds is likely to persist for a while, Kaisa has made investors painfully aware of the vulnerability of their position. So far, offshore bondholders have not had an opportunity to test how they would fare in a Chinese property bankruptcy. Let us hope Kaisa will not give them that chance.

It is also possible that investors would demand tighter covenants on future high-yield bond issues from China. For instance, offshore interest reserve accounts would be one way to address the split between onshore and offshore cash balances – a key concern in times of stress. Such reserves would give issuers and investors more time to sort out problems instead of pushing the issuers into immediate defaults. Investors may also begin to look critically at definitions of change of control and perhaps demand listing suspensions to be included as events of default.

While the underlying structural subordination of offshore bonds is likely to persist for a while, Kaisa has made investors painfully aware of the vulnerability of their position. So far, offshore bondholders have not had an opportunity to test how they would fare in a Chinese property bankruptcy. Let us hope Kaisa will not give them that chance.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed