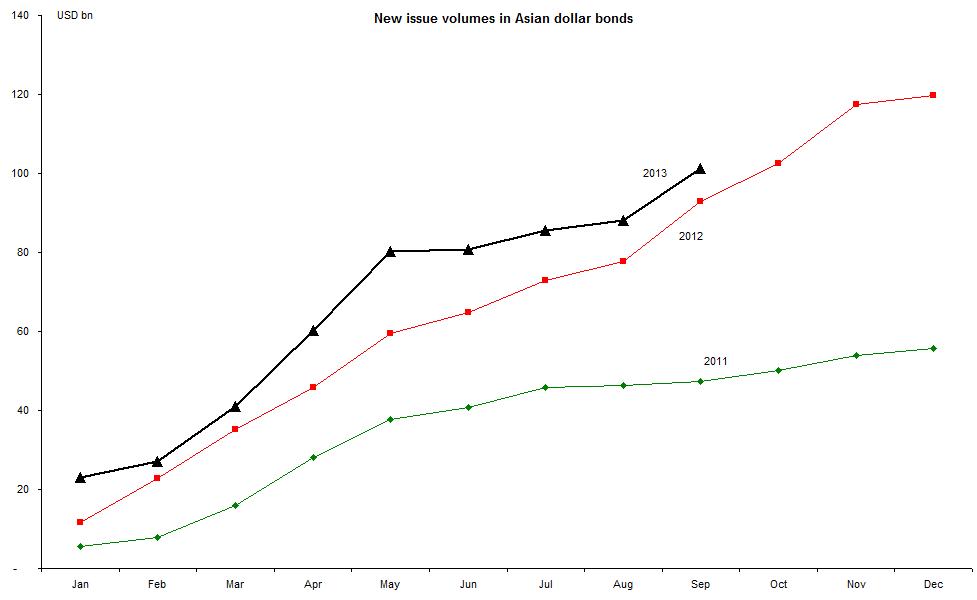

In the midst of all this, Asian bond markets have had a great year in terms of new issues. So far this year, by our count, over USD 110bn worth of dollar-denominated bonds have been issued by Asian issuers. Month after month, in terms of issue volumes, 2013 has outpaced 2012 (which itself was a record year).

What accounts for the robust state of this market? Are investors blithely indifferent to the ructions around them?

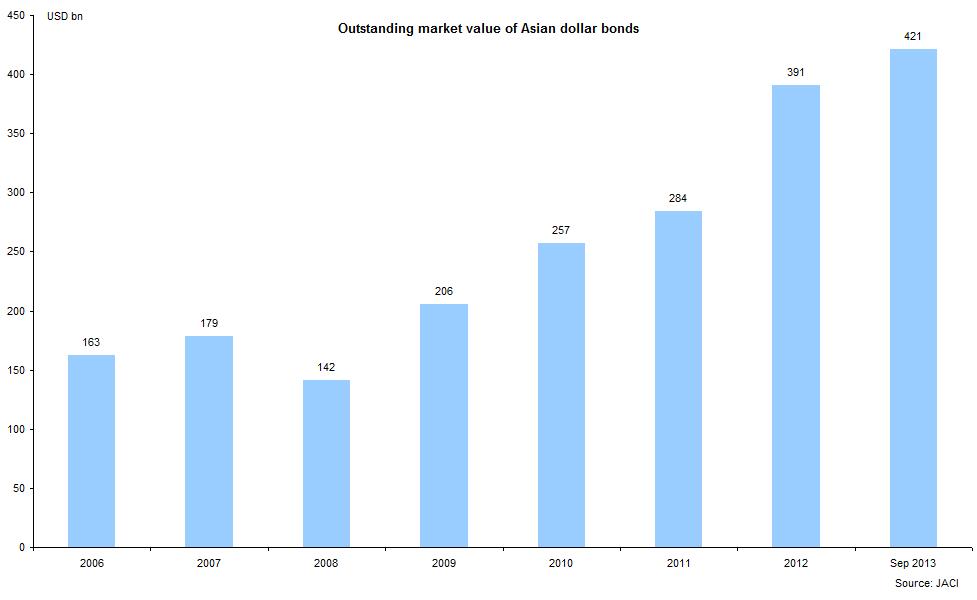

The first thing to recognize is that much of the new issues are simply replacement for maturing bonds. This becomes clear if we consider the increase in the net market value outstanding at the end of the last few years (see chart below). This year, the market value has risen by USD 30bn – not a bad number, but still a slower pace of growth.

At this stage, it is fair to say that Asian dollar bonds have become a legitimate, large asset class with a diversified pool of issuers and sufficient liquidity for investors. Asian dollar bonds represent roughly 40% of all emerging market dollar bonds. Even as interest rates continue their upward journey in the medium term, we believe that institutional money would still be actively engaged in this market.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed