From the investors’ point of view, CNH bonds were attractive because their total return came from not only the underlying bond yield, but also the expected appreciation of the Renminbi. In addition, CNH bonds were less volatile than Asian USD bonds, although less liquid too. Some investors felt they could park their money in CNH and enjoy a steady and superior return.

Investors’ expectations were validated as the Renminbi had climbed steadily at an annual rate of 3.4% against the dollar from August 2010 until January 2014, after being frozen from 2008 to 2010 during the peak of the financial crisis.

But recent developments have shaken the expectations. Since January 2014, in just over 60 days, the Chinese currency has weakened 2.8%. On March 15, the People’s Bank of China widened its daily trading band to 2% around the central value from the previous 1%, raising the possibility of further depreciation in the currency. Whether the currency falls further or not, these changes have raised the volatility of the currency.

The reasons for the currency fall are not far to find. The Chinese economy has been slowing perceptibly over the last two quarters. There are rising concerns over the significant amount of credit creation in the economy. These concerns have led to the exit of some hot money from the currency. There is also the possibility that the currency depreciation may actually be welcomed by the Chinese authorities in the face of slowing exports from China.

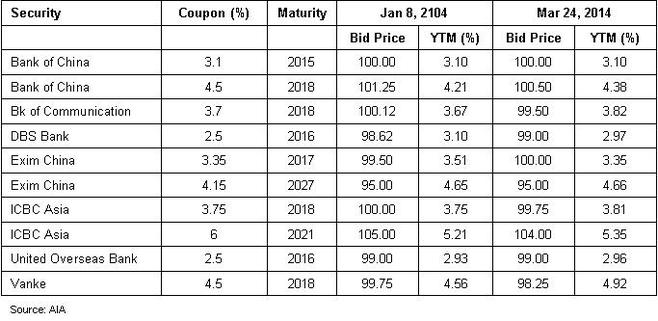

Whatever the reasons, the currency fall has shaken one significant support to the CNH bond market. But the surprising fact is that the CNH bond values have hardly budged in the last two months (see table below). Reflecting that, the HSBC CNH index has held steady from 107.45 at the beginning of the year to 107.81 on March 21. One reason could be that investors, particularly the private-bank investors, view the currency weakness as temporary.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed